It Was Never About the Mileage

I was dismayed and slightly infuriated to find that the GMC Sierra Hybrid has been axed for 2014*, but wasn’t at all surprised.

The problem with the Sierra Hybrid, a full-size pickup truck (and its nearly identical brother, the Yukon SUV), was that it was created for Americans and appreciated only by engineers. When you think about how little pickup-needing construction work most engineers do, that already-minuscule intersection makes for an pretty nonexistent market. In fact, considering GM vehicles are designed by American engineers†, as any current tech school student can attest to.], I’m surprised this kind of marketing disaster doesn’t happen more often‡.

Let me demonstrate. What’s the question that’s been been on your mind since you found out about this hybrid pickup truck?

Yeah, “what kind of miles do you get to the gallon?”

But actually consider the Yukon Hybrid. Compared to a standard similarly-equipped good ol’ internal-combustion Yukon, it’s somewhere between $3000–$6000 more and weighs 262lb. On top of a ~$50,000 sticker and 5694lb curb weight, those are nothing. Here’s what you get in return:

- Two 60kW electric motors, which produce maximum torque at a dead stop (no clutch needed, unlike the IC engine which produces peak torque at 4100RPM)

- A NiMH battery pack that fits under the rear seats, taking up no additional space, and which can provide enough juice to get to 30mph under pure silent electric power

- A continuously variable transmission (CVT) that juggles the torques from the motors to optimize the output of the 6.0L V8

It’s an engineer’s wet dream; the hybrid system truly enhances the vehicle performance in areas that matter to people who buy trucks and SUVs: acceleration (torque) and towing capacity (torque, but also power), without compromise. Heck, older versions of the Sierra even had 120VAC outlets, which is hilariously like having the reverse of a plug-in hybrid system, but seems genuinely useful for e.g. a contractor with corded power tools or somebody living in a remote area with flakey power.

Sadly, consumers and journalists remain strapped to the myth that hybrids must be slow and small, and that their only reason to exist is to save gas, forcing carmakers to pander to that fiction. People simply don’t stop think why you’d build a second traction system into a car; instead, they file away hybrids as it were some expensive, heavy gadget that magically (and only) reduces the amount of gas used.

For example, people expect hybridizing to be appropriate only for vehicles small and light. I mean, if you’re buying a hybrid, you must only want to save gas, and to have extra capacity obviously ruins the entire vehicle. Truth is, it’s actually more difficult and less effective to hybridize a light vehicle—one of the reasons why you don’t see any motorcycles sporting extra batteries and motors—while throwing even a ton (1000 pounds) of batteries, motors, and motor controllers onto anything in our “light truck” category won’t really make a huge difference in weight and space.

⋮

My first knowledge of hybrid trucks was when I spoke to Jerry Meisel, who had advised the Georgia Tech FutureTruck team. For whatever reason, the Department of Energy (DOE) decided more than a decade ago§ to invite university teams to build the most eco-friendly vehicles possible, given a toolkit consisting of a Ford Explorer¶ and $10,000.

Three years after the competition began, the GT team began to miss the point completely♠ and had instead crammed a 150kW motor onto the front of their Explorer, then chose the “largest V6 that would fit” to power the rear axle. Although the “FutureWreck” showed it was capable of “takin’ off like greased lightnin'” at the Michigan proving grounds, it took no higher than fourth place. I’ll let Jerry himself explain why:

“Even though [our entry] really performed better than any other powertrain, [the judges] were looking for designs that had some combination of a diesel engine, the use of an alternate fuel to gasoline and some aggressive weight reduction by replacing the stock steel frame,” said Professor Jerry Meisel. “We more than met the competition’s stated goals in actual operation, but had none of these unstated approaches in our design.”

At least it took home the award for acceleration.

⋮

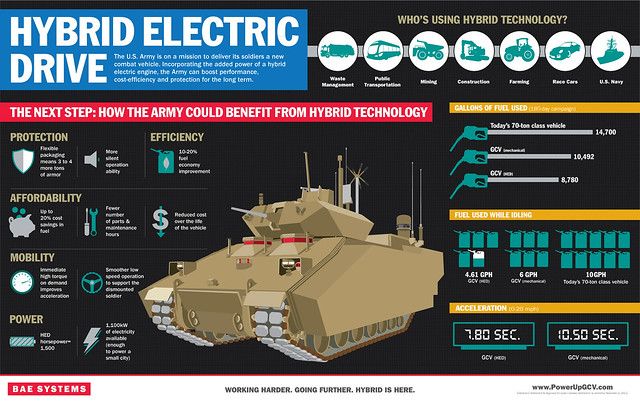

Why the market remains convinced that hybrid systems are for ugly featherweight cars with rubbish names is a mystery to me. Consider this: modern electric traction systems are so powerful, Jaguar built a £1 million supercar where they were the only source of propulsion. General Dynamics and BAE are building armored military vehicles, including even battle tanks, propelled by electric power. Their applications in the military especially highlight the subtler auxiliary benefits of modern motors beyond their unholy torque ratings: flexible power routing, whisper-quiet operation, low parts count, and solid reliability.

In fact, I should note that somebody involved with the General Dynamics project was who had first filled me in on the Yukon. You know who you are—thanks man and sorry for ripping you off. Doing research on this was hard!

⋮

The knee-jerk conflation between “hybrid” and “fuel efficiency,” along with “weak performance” and “sissy,” lead almost directly to the downfall of every past hybrid or electric high-performance vehicle. It even plagues championship-winning Le Mans cars, where the advantage of the electric half isn’t one of fuel efficiency (though increased endurance obviously helps), but is in fact an incredible advantage in any race: the ability to absorb energy otherwise lost to braking, then use it as a boost say, at the exit of a corner. This use even has a name: kinetic energy recovery system (KERS), otherwise known as “regenerative braking.”

Yet the journalists and the media jumps on the hybrid bit like it’s all about saving the planet. Literally:

Engadget: Audi’s e-Tron becomes the first hybrid to win Le Mans, saves the planet at the same time

Guys, I think you still missed the part where they won the race with this tech. They didn’t throw a motor in there to wave their engineering penis around, proving they can win “despite” using a hybrid—even if they are Audi—it was there because it made their car go faster.

⋮

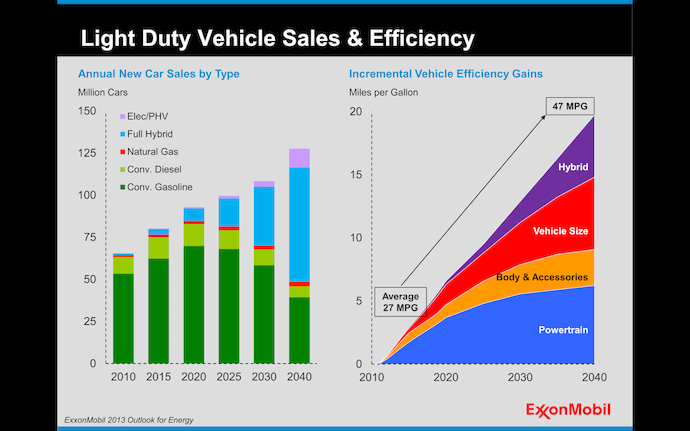

The sooner we embrace electric as the future of auto performance, whether on the racetrack or at the worksite, the sooner their other goal can be met: actually saving the planet. No matter how parsimonious Volts are with emissions, it won’t matter if BEVs and PHEVs are only 5% of the market by 2040. We need people to drive hybrids and then electrics in every sector of the market, from people-carrier commuters to hatchback hoonmobiles to soccer mom armored child delivery systems.

And that’s according to ExxonMobil.